- Emerging PT

- Posts

- Fall Risk Assessment and Prevention in Older Adults

Fall Risk Assessment and Prevention in Older Adults

The Role of Balance Training for the Aging Adult and How to Reduce Fall Anxiety

Why Falls are so Hazardous

Falls are one of the leading causes of morbidity and loss of independence in older adults. Beyond the physical consequences such as fractures, head injuries, or hospitalizations falls often instill a significant fear of falling. This fear can be just as limiting as the fall itself, leading many older adults to withdraw from physical activity, avoid community engagement, and adopt more sedentary lifestyles. Unfortunately, inactivity only accelerates deconditioning, muscle weakness, and balance loss, thereby increasing fall risk in a vicious cycle.

The Subjective History-Ask the Right Questions

A fall assessment begins with a thorough subjective history. Common questions include:

Fall history: Have you fallen in the last 12 months? How many times? Did you lose consciousness or sustain injuries?

2 or more falls in the past 12 months is a significant predictor of future falls and warrants a detailed exam and documentation of said falls.

Circumstances: What were you doing when you fell? Which direction did you fall?

Falling laterally are often considered the most dangerous kinds of falls due to the risk of breaking a hip and not being able to catch oneself.

Medical and medication review: Have there been recent medication changes? Do you take medications that make you dizzy or tired?

Functional screening: Do you use an assistive device? Do you feel unsteady or rely on furniture to walk? Do you have difficulty standing from a chair or climbing steps?

Other risk factors: Do you rush to the bathroom during the night? Do you feel sad or worried about falling?

These questions uncover both direct causes (e.g., trip hazards, fainting) and indirect contributors (e.g., depression, polypharmacy, incontinence).

Systems Inventory: Why Older Adults Fall

alls rarely result from a single issue. Instead, they often reflect impairments across multiple systems required for postural control:

1. Sensory System

Vision: Impaired acuity, depth perception, or contrast sensitivity can reduce hazard detection. Screening tools include Snellen charts and visual field tests can identify these deficiits.

Vestibular system: Loss of gaze stabilization or vertigo affects orientation. Assessed through vestibular/oculomotor testing. Check out our previous article over the vestibular exam if you need a reminder :).

Somatosensory system: Peripheral neuropathy, arthritis, or joint replacements can reduce proprioception and cutaneous sensation. Screen with light touch, vibration, and joint position tests.

2. Central Nervous System (CNS)

Even when the sensory systems are intact, the CNS must accurately integrate and coordinate input to generate an appropriate postural response. Disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, cerebellar dysfunction, stroke, or other neurodegenerative conditions can impair this integration, leading to poor adaptation in balance-challenging environments.

If CNS dysfunction is identified:

Referral: Ensure coordination with neurology or primary care for diagnosis/management if not already established.

Compensatory strategies: Introduce external cues (auditory or visual), environmental modifications, and assistive devices to reduce fall risk.

Restorative interventions: Incorporate task-specific training, dual-task practice, and perturbation-based balance exercises where safe and appropriate.

3. MSK System

Muscle weakness, limited range of motion, and reduced endurance contribute to poor balance responses. For example:

Ankle strategy (first response to perturbations) is weakened by limited dorsiflexion and plantarflexion strength.

Hip strategy (secondary response) depends heavily on strong lateral hip stabilizers.

Screening includes heel rise tests, hip abductor strength testing, and functional measures like 5x Sit-to-Stand

Fall Management Strategies

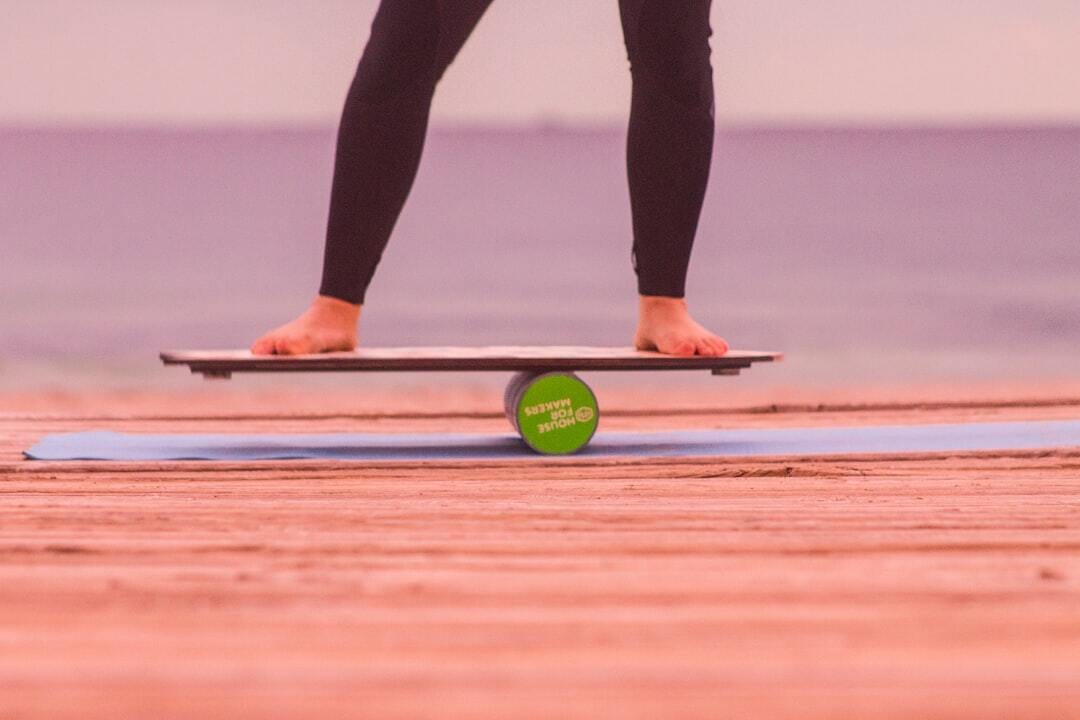

Balance Training: The Evidence

Balance training is one of the most effective interventions for reducing falls. Research shows that:

Exercises must be performed in standing and challenging enough to push the limits of stability. No one gets better when they feel completely steady throughout an exercise. Don’t underdose because of low expectations and uneccessary assumptions.

A minimum dose of 50 hours is needed to see meaningful reductions in fall rates. This equates to about 90 minutes per week over several months, ideally spread across 2–3 days per week.

Training should progress from static to dynamic balance tasks, with dual-task and perturbation challenges integrated as tolerated

The Otago Exercise Program: An At-Home Solution

The Otago Exercise Program (OEP) is an evidence-based, home-delivered intervention designed for frail or homebound older adults.

Program Structure:

Delivered initially through 7 home visits over a year by a physical therapist.

Patients complete exercises independently 3x per week.

Includes both strength and balance exercises targeting lower extremity muscle groups critical for stability.

Dosing & Effectiveness:

Requires ~90 minutes/week, with 3 days dedicated to balance training.

Studies show a 35–40% reduction in falls among participants

Exercises and HEP:

The OEP focuses on progressive lower extremity strengthening and balance exercises, which are then carried over into daily life through the HEP.

Linked here is the full guide on the exercises and HEP program outlined by the OEP.

|

The most effective OEP implementation happens when balance training, strengthening, and functional carryover all align. A good fall risk assessment determines:

Where to start (static vs. dynamic balance, seated vs. standing, amount of resistance).

How to safely dose (intensity, frequency, progression pace).

Which environments to recommend for HEP practice (always near a sturdy surface such as a counter or stable chair).

Safety Considerations:

Because effective balance exercises challenge the limits of stability, patients should practice near a stable support surface (e.g., countertop, sturdy chair).

Progression: reduce hand support gradually (two hands → one hand → fingertip → hands-free) before advancing difficulty.

Parting Words

Falls in older adults are multifactorial, requiring a comprehensive assessment of sensory, CNS, and neuromuscular systems. Prevention hinges on evidence-based interventions like the Otago Program, which emphasize structured balance training at sufficient dose and intensity. With consistent practice (90 minutes per week, totaling 50 hours over time) clinicians can empower older adults to reduce fall risk, maintain independence, and break the cycle of fear and inactivity.

References

Sherrington C, Whitney JC, Lord SR, Herbert RD, Cumming RG, Close JC. Effective exercise for the prevention of falls: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(12):2234-2243. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02014.x

Disclaimer

I am a current Doctor of Physical Therapy (DPT) student sharing information based on my formal education and independent studies. The content presented in this newsletter is intended for informational and educational purposes only and should not be considered professional medical advice. While I strive to provide accurate and up-to-date information, my knowledge is based on my current academic and clinical rotations and ongoing learning, not extensive clinical practice.

Reply