- Emerging PT

- Posts

- The Sixth Vital Sign Unpacked: A Guide to Gait Evaluation

The Sixth Vital Sign Unpacked: A Guide to Gait Evaluation

Breaking Down Gait Mechanics to Improve Clinical Observations and Patient Outcomes.

The Sixth Vital Sign and its Importance

The observation of gait is a critical skill and a trademark of all physical therapists in all settings. Why, you might ask? All people have a unique and/or preferred method of ambulating that gives us insight into how they experience movement through various settings.

Speaking from experience, gait observation can be a daunting skill for many reasons including time constraints, movement complexity and a variety of approaches. Developing this skill occurs differently for all practitioners so it is imperative that you remain positive about what you feel confident in and focus on what barriers to knowledge or approach may be inhibiting your observations.

Many times we can use gait observation to help guide our physical therapy evaluation of a patient. In our training, gait has been referenced as the ‘sixth vital sign’, and for good reason. Certain movement patterns may indicate imbalances in strength or length in major muscle groups or even point towards specific diagnoses altogether. We will explore the basic concepts and sample constructs for gait evaluation.

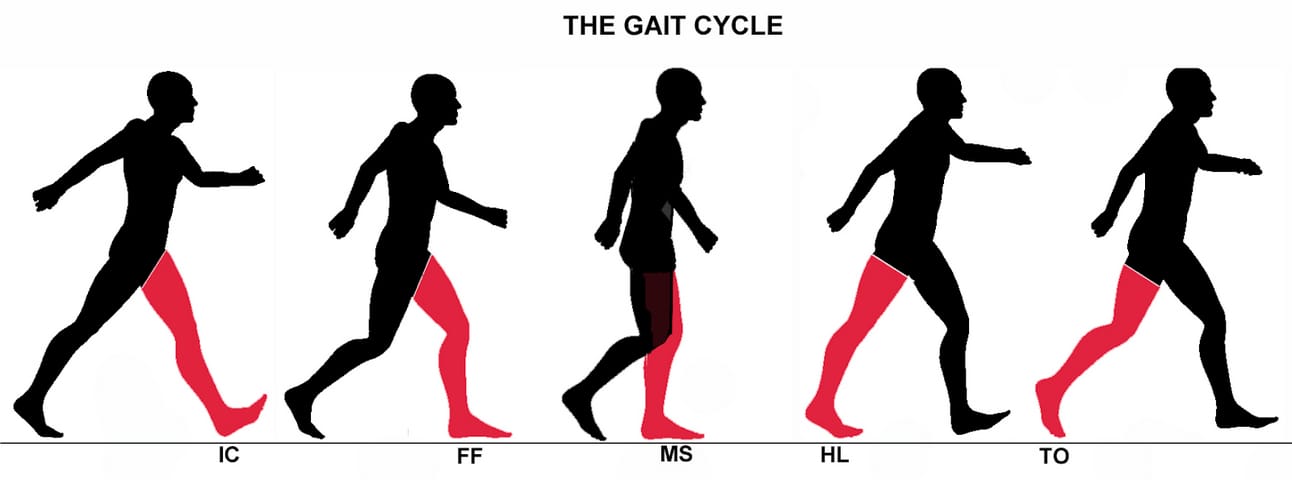

Introduction to the Components of Gait

To evaluate abnormal gait we must first be able to understand the fundamental components of typical gait. The most widely recognized phases of gait consist of the stance and swing components. While this can be helpful to broadly detect where your patient is demonstrating difficulty, we need to dive further into the sub-phases to gain insight into which muscle groups are problematic. Below is a brief description of each sub-phase1 and its major contributing muscle groups in the included chart. This is likely to be review for most of our readers, but it is always beneficial to have a steady footing with this topic before moving forward. I would encourage you to try to recall the various gait components before refreshing your knowledge in the section below if you feel confident in your current skills!

Stance Phase: Period during ambulation where the foot is in contact with the ground. This phase equates to around 60% of the entire gait cycle.

Initial contact (IC): Moment the foot makes ground contact initiating the heel rocker

Loading response (LR): Impact force and body weight is absorbed through the outstretched stance limb while simultaneously initiating stability and limb progression

Midstance (MSt): The stance limb is supporting the full body weight while the person’s center of gravity is directly above the ankle

Terminal stance (TSt): The body has progressed in front of the stance limb, weight is shifted onto the ball of the foot as the heel rises from the floor. The contralateral limb begins its stance phase

Swing Phase: Period in which the foot is not in contact with the ground (40% of gait cycle)

Initial swing (ISw): Moment the foot leaves the ground up until maximal knee flexion occurs

Mid swing (MSw): Maximal hip flexion is achieved to continue progression of the limb forward through space and ensure foot clearance

Terminal swing (TSw): Critical extension of the knee and deceleration to prepare the swing limb to transition to initial contact and loading response

For those of you looking for an in depth dive into the specifics of the subphase mechanics, here is a guide to the major muscle activations and critical ranges of motion necessary for typical gait corresponding with the phases above. I continually reference this chart when trying to identify muscle groups that would be beneficial to target during treatment.

Courtesy of the brilliant mind of Max Gortmaker

Before exploring the common approaches to gait analysis, there are a couple specific numbers that we would like new practitioners to become familiar with. These numbers are important to identify problematic ambulation and locate which part of the cycle it stems from. However, it should be mentioned that these numbers should be related to overall patient presentation and connected back to their primary complaints before being addressed. For example, if you are seeing a patient for shoulder issues, it is not likely that gait training will be a justifiable intervention even if you have noted deviation from these typical values.

Important Average Values Relating to Typical Gait (Adult)

Step width: 2-4in (8cm)

Stride length: 4ft (1.4m)

Toe out angle: 0-10 degrees

Safe household ambulation speed: 0-.4m/s

Safe limited community ambulation speed: .4-.8m/s

Safe community ambulation speed: .8-1.25m/s

Typical ambulation speed: 1.34m/s

Approaches to Gait Analysis

Patients walk, and for those who do not, it is one of the most common goals to hear upon intake and throughout physical therapy treatment. In this section we will explore the two main approaches that practitioners use when analyzing gait. Identifying which approach to use can help guide new practitioners and students streamline their observations. I should mention that each approach mentioned is not meant to exclude the other option as it is likely that you may need to graduate from one approach to another based on patent presentation.

Specific Approaches to Gait Analysis:

Segmental observation model: This is the most common form of gait analysis that involves starting with the most superior or inferior joints involved in the gait cycle and systematically working down/up the chain to identify functional or dysfunctional components. This is the approach that I find myself using most often as it allows for me to break down dysfunctional gait into more manageable chunks that can be addressed. I would recommend looking at each joint level for multiple strides if possible. This allows you adequate time to recognize dysfunction and try to process it in conjunction with the other joint levels. It can be easy for new practitioners and students to get caught up on one joint level using this approach and attribute any gait deviations to it so I would encourage you to make sure you are using each joint level as a piece in the larger puzzle of patient presentation. If you are using the segmental approach I would recommend starting in the same place every time.

Subcomponents model: This model takes a more holistic approach to gait and looks at the different planes of movement as opposed to looking at each joint level. This involves four components: Stance control, limb advancement, propulsion, and postural stability. Stance control refers to the presence or absence of a vertical collapse during the stance phase of a limb. Both limb advancement and propulsion consider sagittal plane motion looking at foot clearance and movement of the center of mass in a specific direction respectively. Postural stability evaluates frontal plane motion looking at the ability to keep the center of mass within the base of support during ambulation. This approach is highly versatile as it captures strength, balance and multi-planar movement as opposed to the more regimented segmental observation style. I personally like to use this method in situations outside of gait analysis such as backwards walking and stepping drills due to its versatility. The largest fault I find with this method is that it does not help practitioners pinpoint problematic structures as well as segmental observation. Faults in these subcategories can be attributed to many structures and require more in depth testing. For the subcomponents approach I would encourage you to use the same order in each situation so that it feels natural.

Methods of Gait Analysis

Given the complexity of gait analysis you may be wondering what tools you have at your disposal to make sure you are practicing at your highest potential and providing optimal care. Within our facility at the University of Missouri, we have access to a motion capture system that allows for instantaneous mapping of force vectors and real time joint angle approximations during gait. But the truth is that in your first clinical or your current place of practice, this technology is often not readily available to help practitioners gather the most objective data. This is where our training and creativity comes into play to provide consistent interpretations of gait performance. The following are common methods of capturing gait data for evaluations and to guide intervention:

Video: I would encourage you to use your (or a patient’s) phone as a resource to video patient performance. This method has numerous benefits such as a frame by frame breakdown where you can show and not tell a patient what you would like to help them improve, slow down movement for careful analysis and document progress.

Functional outcome measures: Many of the functional outcome measures we are trained to administer take into account gait speed and the quality of movement. Can you think of an outcome measure that gives a great excuse and time to do a thorough gait analysis without telling the patient directly that we are going to watch them walk? What about the 6 Minute Walk Test or a 10M Walk Test?

Objective Reports: Resources such as the Edinburgh Visual Gait Score break down the cycle into individual components that are scored based on deviations detected in video analysis. This was originally validated for reliability for gait analysis for persons with cerebral palsy, but it can easily be adapted to evaluate most pathological gait presentations.

Gait Case Study:

Included below is a short video of a patient that is demonstrating an ataxic gait pattern. I would encourage you to take some time to practice your gait analysis skills by watching the video and trying out both approaches. Below I have included a very basic outline of some major dysfunctional patterns. This is meant to serve as a starting point for you to try to expand from with your own observations.

Segmental Approach to Evaluation:

Foot:

Decreased or absent heel strike during initial contact especially without assistive device (bilateral)

Varying step width especially without assistive device

Decreased forefoot rocker during pre swing (bilateral)

Ankle:

Eversion during loading response (bilateral)

Use of hallux extensors to compensate for poor dorsiflexion during mid swing (bilateral)

Pronation to compensate for reduced tibial progression during terminal stance (bilateral)

Knee:

Hyperextension during initial contact and loading response (right more than left)

Decreased knee flexion during initial swing (bilateral)

Hip:

Decreased hip extension during terminal stance (bilateral)

Trunk:

Forward lean throughout entire cycle to maintain forward momentum with assistive device

Decreased trunk stability while walking without assistive device to assist in maintain balance

Increased trunk rotation during initial swing (bilateral)

Upper Extremity:

Used to improve balance and unload of lower extremities throughout gait cycle using assistive device or therapist support

Subsystems Approach to Evaluation:

Stance Control:

Vertical collapse is absent but is likely partially compensated for using knee hyperextension during stance phase

Limb advancement:

Consistently achieved when using assistive device using hallux extensors to assist in dorsiflexion

Propulsion:

Difficulty maintaining a consistent base of support to support the center of mass

Base of support is compensated using assistive device or therapist support

Postural stability:

Difficulty maintaining upright posture in response to sudden changes in direction

After reviewing the video case study, we encourage you to share your observations — what gait deviations stood out, and did you notice any patterns or abnormalities we may have missed? Based on your findings, what initial interventions would you prioritize, such as targeting specific muscle groups or movement patterns? We welcome your insights and alternative approaches in the comments below!

Don’t be Overwhelmed and Rely on Simple Approaches

Becoming an expert on gait analysis is an ongoing process that is never quite complete. Large strides in your observations can be made by identifying the approach that is appropriate for your patient presentation, applying an analysis method that is best suited for your current skill level, and getting repetitions inside and out of the clinic. Keep in mind that every time your patient ambulates in the clinic or even to and from their car, you have an opportunity to observe their gait. As always, consistency is key. The best advice that I can give to you in regards to gait analysis would be to remind yourself what you feel confident in and to remember that you have resources when you need them. When in doubt, bring it back to the basics and the rest will sort itself out as you go. It can be all too easy for new practitioners and students to become overwhelmed in new situations, but with the help of your fellow practitioners and reliable online resources, you are prepared to take on any dysfunctional gait you may encounter.

References

Pierson FM & Fairchild SL. Principles & Techniques of Patient Care. 6th ed. St. Louis: Saunders; 2018.

Disclaimer:

We are current Doctor of Physical Therapy (DPT) students sharing information based on our formal education and independent studies. The content presented in this newsletter is intended for informational and educational purposes only and should not be considered professional medical advice. While we strive to provide accurate and up-to-date information, our knowledge is based on our current academic and clinical rotations and ongoing learning, not extensive clinical practice.

Reply